Recently two papers seemed to turn what we thought we knew about changes in biodiversity on their head. These papers by Vellend et al. and Dornelas et al. collated data from multiple sources and suggested that species richness at local scales is not currently declining. This was counter-intuitive because we all know that species are going extinct at unprecedented rates. However, it is possible that the introduction of non-native species and recovery of previously cultivated areas may offset extinctions leading to relatively little net change in local species richness.

This week a paper has been published that calls these findings into question. The paper by Andy Gonzalez and colleagues published in the journal Ecology, suggests that there are three major flaws with the analyses. These flaws mean that the answer to the question ‘Is local-scale species richness declining?’ currently remains unanswered and is unanswerable.

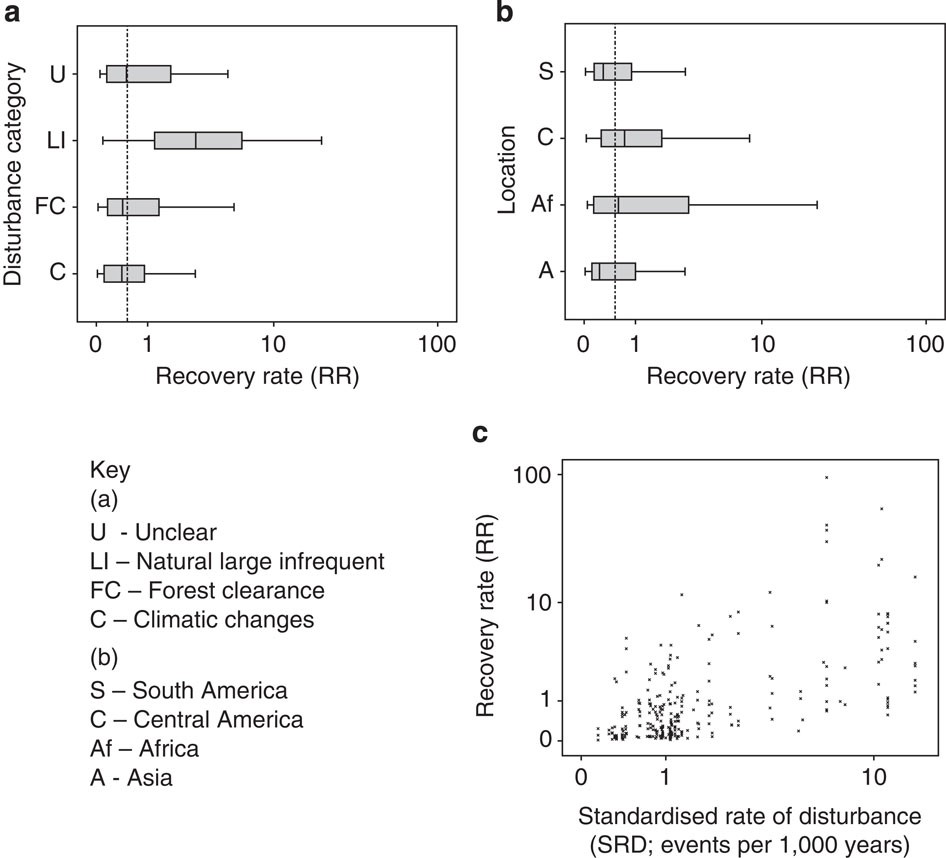

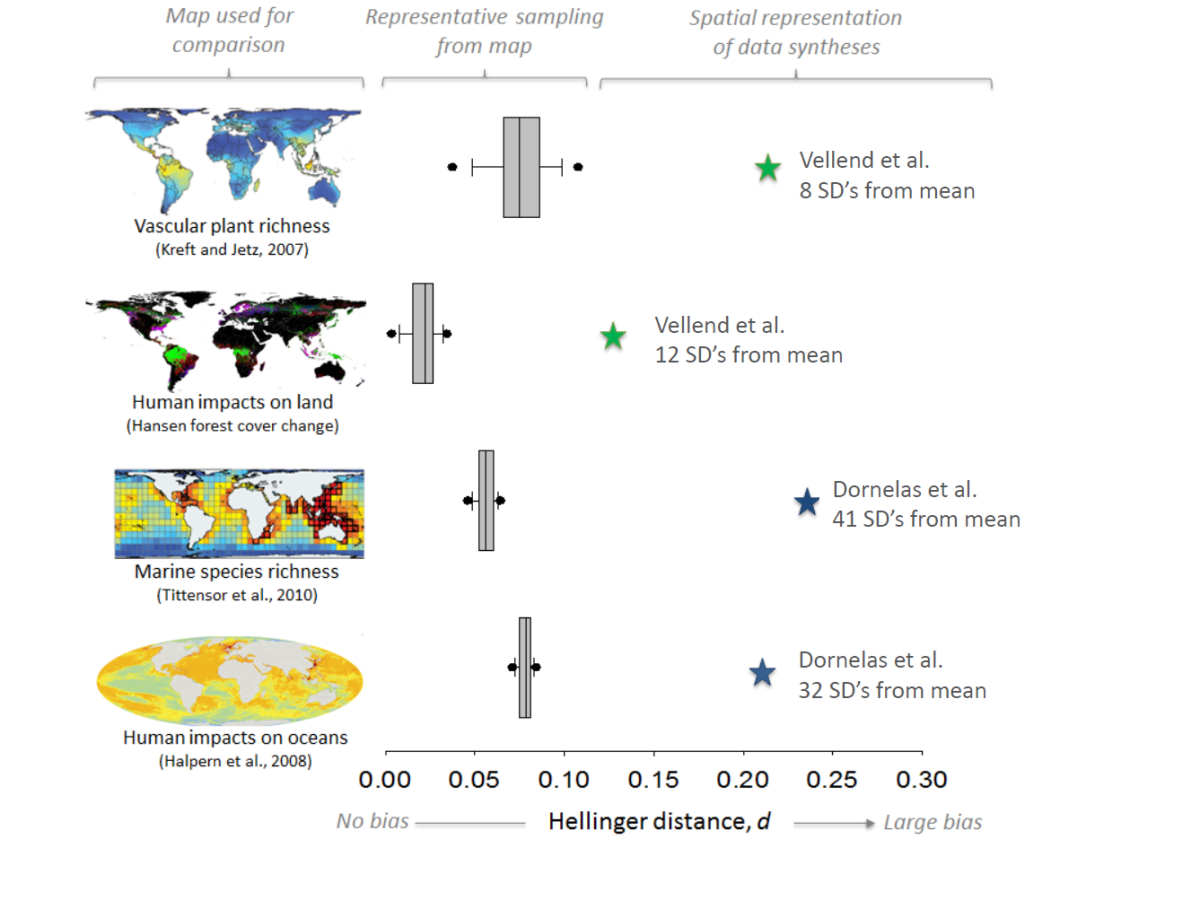

The papers of Vellend et al. and Dornelas et al. were meta-analyses of previously published papers. One issue with meta-analysis is that it is very prone to bias. Like any study if the samples (in this case ecological studies) are not representative of the population (in this case locations around the globe) then any results will be flawed. To test the representativeness of the datasets used by Vellend and Dornelas Gonzalez et al. examined how well they represented biodiversity and threats to biodiversity. This analysis (see below) showed that the papers were not representative of biodiversity or the threats faced by biodiversity (though curiously, the analysis of Dornelas et al. showed an overrepresentation of areas highly impacted by human impacts).

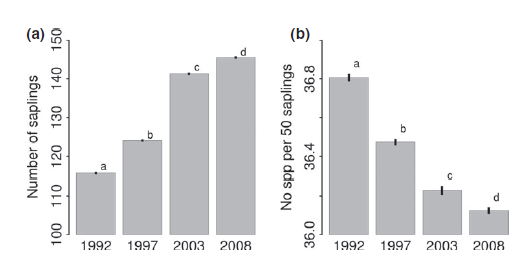

The paper also suggests that using short time series can underestimate losses. By analysing the effect of study duration and changes in species richness (see below) Gonzalez et al. claim that increases in study duration were correlated with a decline in species richness. This supports previous theory which suggests that there is often a time lag between disturbance events and species extinctions – termed ‘extinction debt.’ However, I’d be intrigued to see the results of removing the studies with the longest duration from this analysis since the authors admit that the analysis is sensitive to their inclusion. I’ve seen recent similar work that suggests the same kind of relationship might be seen for studies monitoring individual animal populations.

Thirdly, Gonzalez et al. assert that including studies in which ecosystems were recovering from disturbance (e.g. regrowth on former agricultural fields) without taking into account historical losses that occurred during or after the disturbance biases estimates of change. The paper by Vellend et al. in particular combined studies of the immediate response of biodiversity to disturbances such as fire and grazing along with studies of recovery from the very same disturbances. Gonzalez et al. show that once studies of systems that were recovering are removed from Vellend et al’s analysis there is a negative trend in species richness changes.

The biases prevalent in the Vellend and Dornelas papers lead to Gonzalez et al. to suggest that the papers cannot conclude what the net changes in local species richness are at a global scale. However, they note that the results of Dornelas and Vellend are in sharp contrast to other syntheses of biodiversity changes which used reference undisturbed such as those by Newbold et al. and Murphy and Romanuk which reported average losses of species richness of 14 and 18% respectively.

In their conclusion Gonzalez et al. suggest that though meta-analysis is a powerful tool, it needs to be used with great care. Or to put it another way, with great power comes great responsibility. As someone who regularly uses meta-analysis to form generalisations about how nature works I completely agree with this statement. Traditionally scientists have used funnel plots (graphs with study sample size on the y-axis and effect size on the x-axis) to identify biases in their analyses. I’ve always been skeptical of this approach, especially in ecology where there is always a large amount of variation between sites. In the future syntheses would do well to follow the advice of Gonzalez et al. and really interrogate the data they are using to find any taxonomic, geographic, climatic or any other biases that might limit their ability to generalise. I know it’s something I’ll be taking more seriously in the future.

Gonzalez et al. also point out that most ecological research is carried out in Europe and North America. If we want to monitor biodivesity we need to increase efforts in biodiverse tropical regions, as well as boreal forests, tundra and deserts. We need to identify where these gaps need filling most and then relevant organisations need to prioritise efforts to carry out monitoring. I am positive that this can be achieved, but it will cost a lot money, needs to be highlighted as a priority and will ned a lot of political good will. Even with this effort some of the gaps in biodiverse regions, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, will be extremely difficult to fill due to ongoing armed conflict

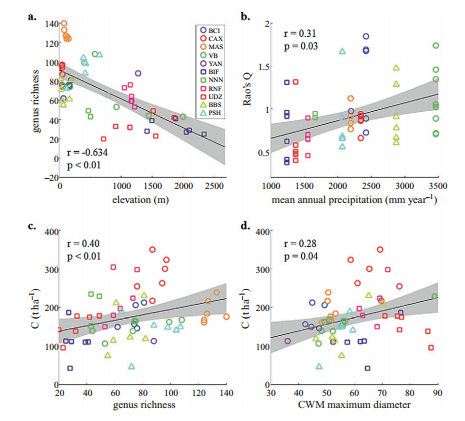

My take-home message from this paper is that we need to be more careful about how we do synthesis. However, I also think that species richness isn’t the only metric that we should focus on when talking about biodiversity change. Studies have shown that measures of the traits of species present in a community are generally more useful for predicting changes in ecosystem function than just using species richness. Species richness is the iconic measure of biodiversity, but it probably isn’t the best. Ecologists should view species richness in the same way as doctors view a thermometer – it’s a useful tool but you still need to be able to monitor blood pressure, take biopsies and listen to a patient’s lungs before you diagnose them*.

*Thanks to Falko Bushke whose analogy I stole from a comment he made on my blog post here.